Bookshop

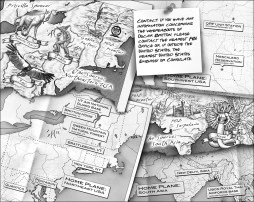

The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, which I reviewed on Tor.com last year, has won a World Fantasy Award for its editor, Huw Lewis-Jones.

The 2019 World Fantasy Awards were announced yesterday at the World Fantasy Convention, held this year in Los Angeles; Lewis-Jones won in the Special Award—Professional category.

Winners in each category are decided by a panel of judges.

Previously: The Writer’s Map; More from (and on) The Writer’s Map; Essays on Literary Maps: Treasure Island, Moominland and the Marauder’s Map; David Mitchell on Starting with a Map.

An exhibition at BNU Strasbourg,

An exhibition at BNU Strasbourg,